Doctor Who and the High Stakes Drama of Douglas Adams

Douglas Adams' time on Doctor Who may be known for its rampant silliness, but there were dark, dramatic ideas beneath the absurdity...

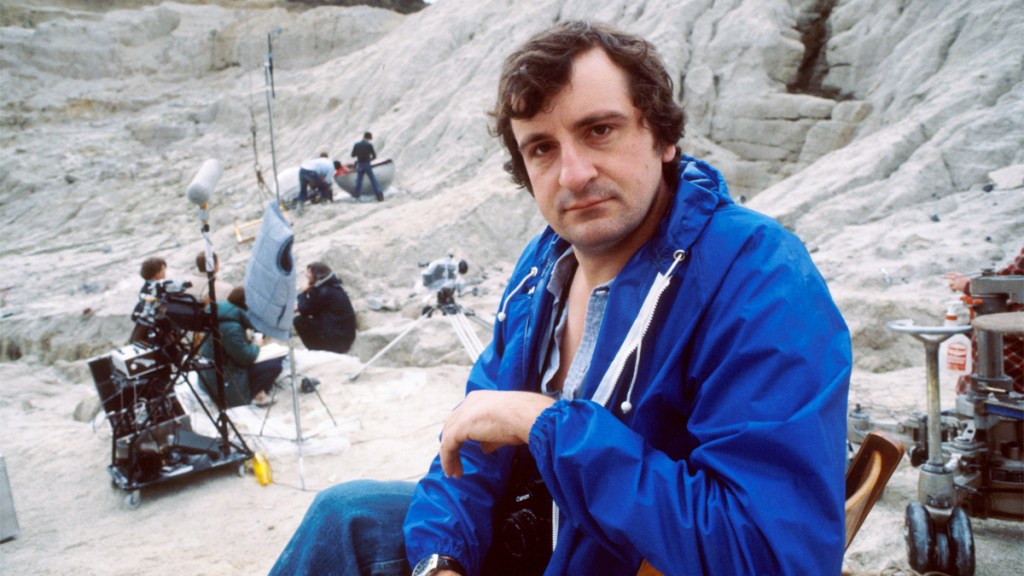

In Doctor Who terms, Douglas Adams will be forever remembered as the co-writer of ‘City of Death’. To fans, he’s the purveyor of undergraduate humour, a man who despaired of actors doing funny walks and silly voices when presented with jokes in a script. Thanks in part to an extreme and vocal reaction against Adams’ comedy from the production team that followed, his reputation is one of rampant silliness that made it hard to take the show seriously.

And yet, in his first ever script for the series, Adams wrote about a vampire planet that materialised around other planets and drained them of all their resources, killing the entire population. In a particularly vicious detail, the remains of the planets are kept in a trophy room. This wholesale slaughter founded a life of comfortable complacency for the unquestioning citizens. The whole point of this, it transpires, is to keep an ancient and dying monarch from death.

It produces the Doctor’s justly lauded ‘But what’s it for?’ outburst in response, and it had to. In 1978 this was the largest scale of destruction seen in Doctor Who. While the ideas involved came from several different script ideas (one involving the Time Lords being the planet-sapping aggressors), the final product acknowledges the sheer horror of the ideas in ‘The Pirate Planet’.

However, Head of Serials Graeme McDonald disliked Adams’ scripts enough to ask producer Graham Williams to scrap it entirely, because he thought it was too overtly humorous.

Before we go on to examine the ideas in Adams’ scripts, it’s worth stating that his scripts are ostentatiously comedic as that’s just his default writing style, but if you think Doctor Who only works at a superficial level then you’re missing out on a lot. Adams is closely linked with Monty Python. He wrote and appeared in the television show, and then proceeded to write with Graham Chapman. He once said “I wanted to be John Cleese, and it took me some time to realise that the job was, in fact, taken.”

So it’s not a huge shock that his comedy is hugely influenced by Monty Python, in particular using absurdity to reflect and mock people. Cleese and Chapman could play authority figures, and make them ridiculous, but everyone was considered fair game. Python used genre clichés and used the grammar of television, playing everything at a heightened pitch. The result is like seeing your reflection in an underground train window – it’s reality, and it’s askew, stretched, ridiculous – but it feels close.

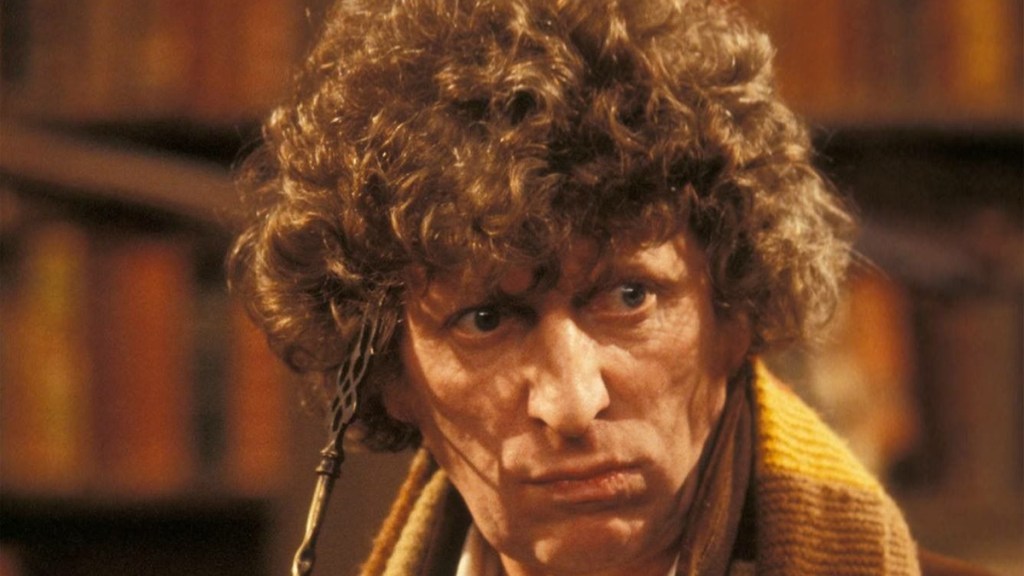

Doctor Who had used this technique before Adams, most notably in the work of Robert Holmes, but rarely had it been so ostentatiously comedic before. Holmes’ work is more obviously cynical and bleakly funny, whereas Adams’ has a silly surface layer and less abrasive Tom Baker performance. However there is still a cynicism to it, the ideas driving the stories are serious, and comedy is used to highlight the absurdity of the situation before providing a more drastic tonal shift. Consider the difference between Eurovision being full of sincere and heartfelt messages of togetherness – which isn’t dissimilar to normal – and Charlie Brooker putting on his Earnest Hat in Antiviral Wipe. The latter has an impact because it’s less expected.

There’s a poem by Caroline Bird called ‘A Surreal Joke’ which addresses Bird’s ostensibly whimsical style as being a way to write about trauma and darkness in a way which is accessible and light. Similarly with Adams he addresses existential despair, mass destruction and genocide with such lightness of touch you almost don’t notice.

Generally Doctor Who stories don’t bring comedy to the fore, it’s in lower in the mix but still present, so Adams’ work sticks out. ‘The Romans’and ‘The Myth Makers’ are exceptions, and the latter successfully uses some of the techniques in ‘The Pirate Planet’, but it wasn’t until the Williams era (12 years later) that comedy was brought forward regularly.

This wasn’t simply an aesthetic choice, but one forced upon the show after the double blow of the BBC caving in to the demands of Mary Whitehouse, and the budget overspends at the end of Season 14 coupled with the financial situation in the UK. Intense and sustained horror imagery was heavily discouraged, while it was simply not possible to spend money on action, sets and costumes to the same extent as before. Tom Baker’s preference for comedy also played a factor (and once Lalla Ward came in as Romana she and Baker would rewrite their dialogue, such as the ‘It has a bouquet’ scene from ‘City of Death’), so it was higher in the mix than before when Adams started writing for the show.

Now it’s simply part of the show’s makeup. People expect Doctor Who to be funny, and using comedy as a diversion or for tonal dissonance is a regular occurrence. In the late Seventies, Adams had less control over how it appeared on screen, but his approach would have fitted in seamlessly after 2005 when other fans-turned-writers became show-runners.

Adams was, on one level, more of a fanboy than his work suggests. For ‘Shada’, a story memorably described by Keanu Reeves as ‘That’s quantum baby’ (NB. Some dramatic licence has been taken here), Adams was interested in exploring what the Time Lords’ version of capital punishment would be. For ‘Destiny of the Daleks’ Adams and Williams asked Terry Nation to base his script on an Isaac Asimov short story, and he brought Christopher Priest (author of The Prestige, later filmed by Christopher Nolan). For ‘Nightmare on Eden’Adams encouraged Bob Baker with the drugs and addiction parts of his storyline. All of which sounds more like something you’d expect from the Nineties New Adventures book line than the late Seventies.

He also edited out gags from David Fisher’s scripts for ‘The Creature from the Pit’and ‘The Horns of Nimon’ – an outlier in terms of Adams’ approach – was made simply because all the other story ideas proved unworkable (a script written by John Lloyd was abandoned when Lloyd became the producer of Not the Nine O’Clock News and nobody else could successfully redraft it, and Pennant Roberts’ ‘Erinella’– influenced by Celtic folklore – was deemed too expensive).

‘City of Death’ is considered the high point of Adams’ work on Doctor Who, and certainly you’d be forgiven for coming away from it going ‘What a fun romp’, but consider the ramifications if the villain’s plan succeeds: humanity will never have existed, thus rewriting the timelines hugely and massively changing the Doctor’s past. This is, as they say, a lot.

Beneath all the froth and wit there’s a villain with a strong motivation, a treatise on art, and the possibility of huge and terrifying changes to time itself. And Doctor Whowas probably the best outlet for Adams because, generally speaking, it doesn’t do things like destroy billions of children because someone is incredibly angry.

Adams’ other works, however, absolutely do. His Hitchhikers book series ends with Mostly Harmless where the free-spirited, Sixties-influenced guide gets bought over and used – with a combination of chance, misunderstandings and the most complete cynicism – to destroy all possible versions of the Earth. The death of the optimism of the Sixties, where Monty Python was born, is complete. The other lot won. And this how some Python-inspired comedy turns out: everything is ridiculous, it says, and society is a façade the same way our silliness is. So why, really, should anything matter? Our only options are to take the piss or to give in to nihilism.

But in Doctor Who, Tom Baker walks away punching the air. Someone gets angry. Somebody does something. And that’s a constraint that we sometimes need.